|

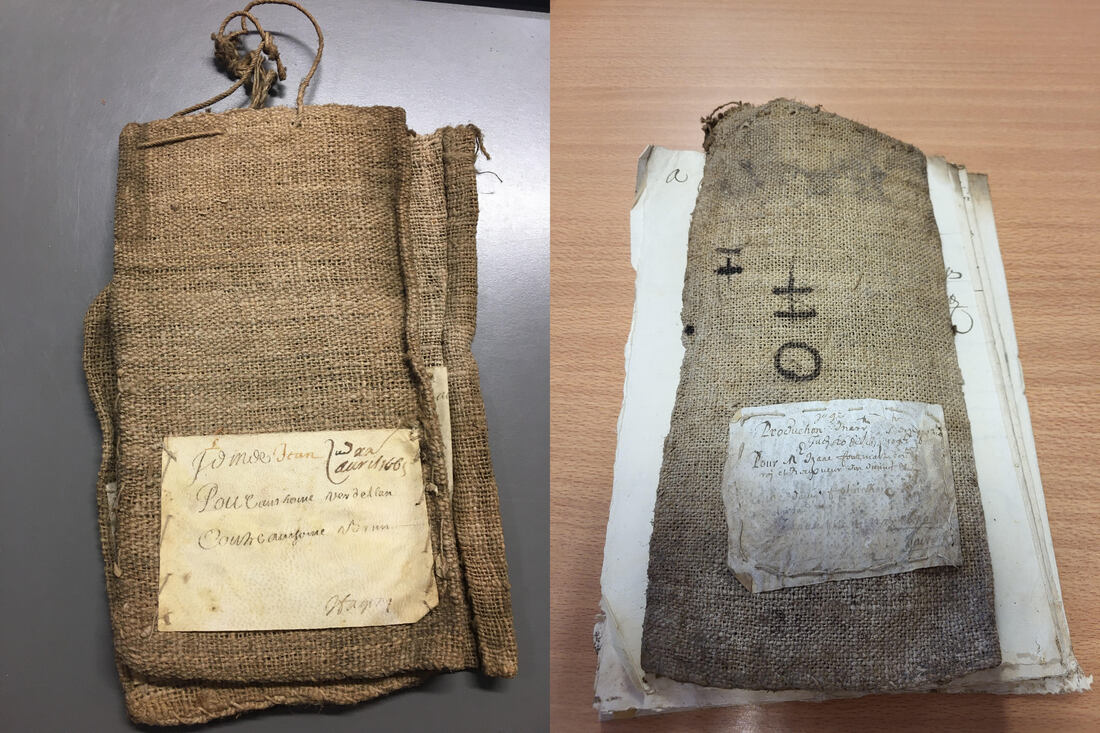

For five months I worked on the sorting, conservation, and cataloguing of trial bags in the Archives départementales de la Haute-Garonne (see also Archive diary of a PhD student – Part 2), as part of Sherilyn Bouyer's research project on the Chambre de l’Édit of Castres. The collection, transferred in 1955 to its current premises, was literally piled up in the current court of justice of Toulouse, previously the location of the Palais du Parlement. In the late eighteenth century, François Garipuy, a Toulouse astronomer and engineer, wrote a description of the palais and already noted the deplorable state of the documents, which he found “covered with dust and debris, almost rotten or devoured by rats.” Throughout the nineteenth century there were several attempts to catalogue the documents, but these were all abandoned due to the magnitude of the task. It was only in the late 1960s that the archives départementales were able to rely on the work of researchers and students to carry on the task of classifying all the trial bags. The endeavor remains colossal to this day, as it is estimated that 100,000 bags are currently stored in the archives. Around 15,000 of these bags have been inventoried since the late 1960s. As a result, today's archivists are faced with bags that are either partially classified – bags loosely tied together to form bundles of bags and scattered papers – or piled up in total chaos. Unfortunately for us, the bags from the seventeenth century, which would interest Sherilyn, are part of this chaos. Before I started my mission, Sherilyn had fifty-one bags pertaining to the Chambre de l’Edit. Therefore, my problem was both very simple and very complex: how to find as many bags from the chamber as possible within the limited time frame of five months? The unsorted mass of trial bags in the Palais du Parlement in 1955. Photo: Archives départementales de la Haute-Garonne. My first reaction to the magnitude of the task was to reflect on these previous attempts at classification. Was it possible that at some point in time bags from the Chambre de l’Édit had been shelved together? The idea did not seem absurd, and my hope from the beginning was to find a cluster of chambre bags, however small it might be. Discovering this hypothetical bundle required a systematic approach. Obviously, the first rule I followed was to consistently pick the bags next to the one I had chosen in the first place. The second approach involved covering the entire unit of four rows, in case a corner was dedicated to the chambre. To that end, I acted methodically to extract the bags. First, I simply noted the number of bags I had processed on each row in a notebook, indicating the location of the bags from the Chambre de l’Édit. I completed a full tour of the unit that way. Then, I improved this method by proceeding shelf by shelf, using an Excel spreadsheet and focusing on the places where I had already found bags from the Chambre de l’Édit. Finally, my strategy was to act efficiently to browse through as many bags as possible while producing solid and meticulous archival work. The archival work can roughly be divided in two parts. One is material, namely to improve and ensure the proper preservation of documents. The other is intellectual, meaning the analysis and cataloguing of the documents, ensuring their discoverability in the database of the archives, which researchers can consult. Although time was a problem, these two tasks had to remain my priority; I couldn't just take the documents out of their bags in search of Protestants. Regarding the preservation of the documents, one of my fundamental tasks was dusting. To not compromise the condition of the documents (dust can contain dormant mold), dusting had to be very meticulous, even if it was the most time-consuming task: dusting was carried out, page after page, on more than 4,000 documents (which could be between 2 and 60 pages). It takes about 10 to 45 minutes to dust off one bag, depending on the number of documents inside. To avoid losing too much time, then, the right bag should not be too heavy. However, if the bag is too thin, the task of analyzing and indexing could become a nightmare, especially if it contains only illegible documents or documents with little information. Moreover, a bag containing only two procedural pieces can be particularly disappointing for the researcher. The second part of my mission – analysis and indexing – has evolved significantly since the 1970s. Genevieve Douillard, former deputy director of the archives, and Jack Thomas, researcher and current president of the association Amis des Archives de la Haute-Garonne, first structured this procedure in the 1990s. Computerized since 2006, the significant work of Jean Maurel on criminal cases from the eighteenth century has shaped the current indexing sheets. The fine-grained indexing of facts, locations, and different levels of jurisdiction are the fundamental pieces of information he contributed to the specialized database that was made available for researchers. In addition to the (sometimes difficult) paleography, the art of good analysis and indexing lies in the archivist's ability to not to delve too deeply into details while still providing the most relevant information. While it was occasionally frustrating not to be able to continue analyzing certain bags, considerations of time and quantity had to remain my priority. It took me some time to figure out how to provide enough information without overdoing it, all the while remaining as meticulous as possible. An untreated trial bag and document (left); the same bag and document after conservation (right). Photo: Brandon Robidet. Unable to skip dusting and indexing, carefully considering my choices in the storeroom (where the bags are kept) was the only way to save time. Were there elements that distinguished, by their external appearance, the bags of the Chambre de l’Édit from the bags of the Parlement? With Sherilyn's help, I tried to carefully observe each of the photos she had taken during her research in the reading room. Certain elements quickly stood out: the canvas of a chambre bag is lighter, the parchment of its label (known as the évangile) surprisingly white, and the layout of its text much less standardized. These few criteria were enough to guide my eye in the storeroom. Markings and parchment labels (évangiles) on the trial bags. Photo: Brandon Robidet. In total I processed 462 bags during my five-month mission. Among these, eleven were produced by the Chambre de l’Édit and four by the Parlement of Toulouse directly concerning the chambre. At first glance, the number of cases of the bipartisan court seems negligible given the classified volume, but it still enriches Sherilyn Bouyer's source corpus by nearly 20%. With more time and resources, I am convinced that a larger cluster of bags from the Chambre de l’Édit could be found. Unfortunately, the regular processing of trial bags only occurs at the rate of one month each year, by students of the master in early modern history, who are not specialised in the history of the Parlement and the Chambre de l’Édit. This raises real conservation questions for documents that — at the current processing rate — will have to wait nearly 200 years to be all treated. This is the reason why the exceptional funding from the University of Groningen provided an important impulse for cataloguing by the Archives départmentales de la Haute-Garonne. It was also a chance for myself to work with these precious sources, but above all for research and for this wonderful collection, whose richness has, so far, only been scratched at the surface. – by Brandon Robidet, Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès

0 Comments

On 22 June, our team organised a workshop in collaboration with the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in The Hague. We gathered historians and practitioners of transitional justice to discuss past and present transitional justice strategies. Our first aim was to better understand how we can evaluate the successes and failures of transitional justice. The second objective of the workshop was achieved in the last session, where we brainstormed about best practices to teach transitional justice to secondary school students – this will be the public outreach component of our project. To do so, we invited two experts at applying science in classrooms. Participants at the workshop. Photo: Rosanne Baars. In the day’s first session, three historians discussed transitional justice strategies used in the past and reflected on what we could learn from them. Nanci Adler (NIOD) opened the session with a presentation of failed transitional justice after the collapse of Soviet Russia: the new regime did not prosecute the crimes committed during the Stalinist era. Her case study led her to conclude that cultures of repression persist long after the oppressors are removed. In other words, the legacy of conflict and an oppressive regime, and of those responsible for the abuses, still exert power over the post-conflict society. Berber Bevernage (Ghent University) continued the session with a presentation on the commission of inquiries set up by King Leopold II of Belgium in 1904. This public enquiry, not unlike our modern-day truth commissions, was to look into the atrocities committed during Leopold’s personal rule over Congo. Bevernage called the commission a “successful failure”, which led to a discussion of how we should evaluate successes and failures, and how perceptions of success may evolve depending on a short-term or long-term evaluation. Sherilyn Bouyer (University of Groningen) concluded the session with her case study: the bipartisan courts set up by France in the aftermath of the French Wars of Religion (1598). She assessed how the historical example of the bipartisan courts can inform today’s scholarship of transitional justice, especially when it comes to evaluating the long-term performance of transitional justice mechanisms. After a well-deserved lunch break, the second session welcomed experts in the field of transitional justice, who discussed more recent case studies. The aim was to address the burden of memory in transitional justice practices. Based on a case study of Sri Lanka, Shyamika Jayasundara (ISS) raised several important issues. She discussed the different scales of transitional justice – the “small” daily justices and the top-down justice of the UN – and addressed the coloniality in transitional justice enterprises. Jayasundara also warned that communities may hold very different perceptions of time as well as memories of conflict, which means that notions of moving forward are not uniform across societies. Transitional justice may not be a linear process, but can also follow a circular rhythm. Niké Wentholt (University of Humanities) followed with a presentation of the current project she is part of, “Dialogics of Justice”. Presenting cases of petitioners seeking historical justice through civil proceedings in Dutch courts, she discussed how the law could be mobilised to bring stories of victims to light and legitimise their truths. Courts are thus a forum where historical narratives are created, and where memories are mobilised. Marc Padberg, founder of Deep Dialogues, concluded the session. Specialised in mediating collectively traumatised environments in a variety of settings, Padberg told the audience how the practices he used to discuss and address trauma in group sessions. Notably, he suggested different conditions required for collective healing. The day’s last session was divided in two parts. First, Paula O’Donohoe (Euroclio) and Joanne Schuitemaker (Scholierenacademie Groningen) represented institutions specialised in designing interactive and engaging history lessons for different age groups. Euroclio specifically specialises in offering guidance for teachers who are educating students about difficult pasts, such as the Holocaust. In the second part of the session, we asked all attendees to think of best teaching practices to educate children about conflict, peace, transitional justice strategies, and the burden of memory in post-conflict narratives. Our team gathered ideas and suggestions which will be put to good use when we prepare a lesson program on past transitional justice strategies, to be used by secondary school students. PI David van der Linden concludes the day. Photo: Rosanne Baars. We went home with many new thoughts, questions, and ideas for the continuation of our project. Discussing the state of the field of transitional justice, the successes and failures of implemented strategies, and the burden of memory has been hugely beneficial. One of the main takeaways of the workshop was the focus on local communities and the different impact transitional justice strategies can have on these communities. The main question remains how the impact and meaning of transitional justice evolves across generations – which is precisely what our project aims to investigate. – by Sherilyn Bouyer

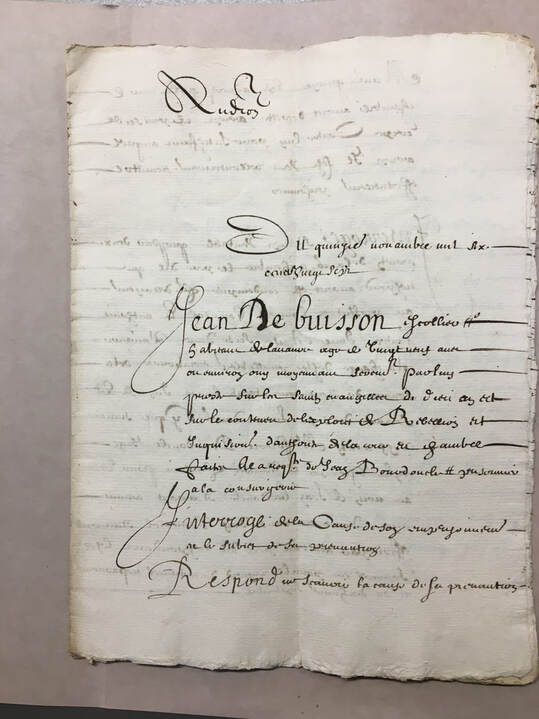

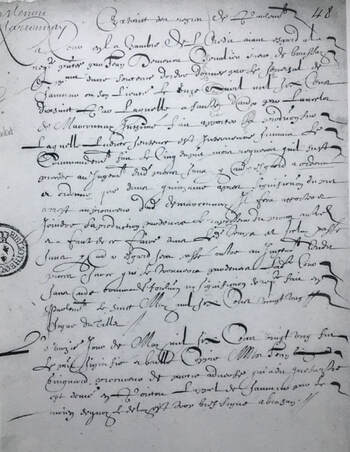

On my first day in the Archives départementales de la Haute Garonne, I opened my first trial bag. This was the beginning of an adventure that took David and me to Lavaur on a sunny November day. Located 30 minutes away from Toulouse, Lavaur is a small town where in 1627 a conflict erupted between Louis de Buisson and the heirs of Raymond Garrigues, which brought them to the Chambre de l’Édit. The trial bag contained just three documents: a witness testimony and two hearings. The witness testimony was part of the case heard by the Chambre de l’Édit, which informed us of the reason of the trial. The object of dispute was a house, which used to belong to Raymond Garrigues. Upon his death, sometime before 1600, the house was supposed to be inherited by Anthoine Vintrou and Honoré Bouniol, but according to several witnesses a certain Louis du Buisson, a lawyer in the town of Lavaur, seized the house for himself. This is when Jean Bourdoncle intervened. A noble of the town of Fiac, a small community just outside of Lavaur, Jean Bourdoncle petitioned the Chambre de l’Édit on behalf of the heirs of Garrigues to obtain ownership of the house in Lavaur. The witnesses, who swore a Catholic oath, all testified against Louis du Buisson, asserting in vivid detail that the latter had completely trashed the house. The Impasse du Boeuf in Lavaur, where the disputed house was located. Photo: David van der Linden. The next two documents were hearings of two men involved in a second incident, which occurred a few weeks after the initial sentence of the Chambre de l’Édit. According to the first hearing, the Chambre de l’Édit had ruled that Louis du Buisson had to hand over the house to the heirs of Garrigues. The second incident opposed Jean du Buisson, the son of Louis du Buisson, and Paul Bourdoncle, the son of Jean Bourdoncle. Although these hearings described the incident from different perspectives, both agreed on the fact that a fight had broken out between the two men regarding the house, which Louis du Buisson allegedly refused to surrender. Hearing of Jean du Buisson by the Chambre de l'Édit, 15 November 1627. Source: ADHG, 3B 56. Photo: Sherilyn Bouyer. After this first read, there were many unresolved questions. We wondered in particular who the Protestant in this case was. Each person interviewed had sworn a Catholic oath, but the intervention of the Chambre de l’Édit suggested that at least one of the people involved had to be a Protestant. This is why we assumed that Louis du Buisson was the Protestant litigant in this affair, as the Catholics witnesses had united against him and were in favour of the claimant. Louis du Buisson was also the one we had the less information about. Furthermore, we did not know much about Lavaur during the Wars of Religion. These questions – and our sheer curiosity about this intriguing case – prompted us to visit Lavaur, and in particular the municipal archive, located in the town’s library. We had made an appointment with the curator at 9h30 on a Monday morning. We had enough time before to take a stroll around the town, with a precise mission in mind: finding the house which caused the dispute almost 400 years ago. While doubts remain on the precise location of the house (we did find the street though), our walk allowed us to discover the beautiful cathedral of Lavaur. In front of the church we encountered a statue commemorating the “town’s deliverance from the plague in the fourteenth century and from the Protestants in the sixteenth century by the intervention of Mary”. The tone was set. The statue of Mary in front of Lavaur's cathedral, thanking her for the "delivery from the Protestants" during the Wars of Religion. Photo: David van der Linden. Our visit to the archive confirmed that Lavaur was indeed a Catholic stronghold throughout the seventeenth century. Our mission was threefold: tracking down the mysterious Protestant in our case, obtaining more information about the house, and contextualising the case by finding out more about Lavaur in the 1620s. Thanks to the parish registers, the cadastral register, and the deliberations of the consulat (town council), we had a productive day with many questions answered. I also have to acknowledge the curators of the archives, who were happy to help us with our queries. At the end of the day, however, our main question – who was the Protestant litigant? – remained unanswered, as we quickly find out, to our surprise, that Louis du Buisson was a Catholic and an important person in Lavaur, who served as consul on the town council. The search is therefore not over. What’s most important, however, is that this excursion to Lavaur showed the opportunities of local research, preparing me for future expeditions into other towns of the Midi where cases heard by the Chambre de l’Édit happened. – by Sherilyn Bouyer

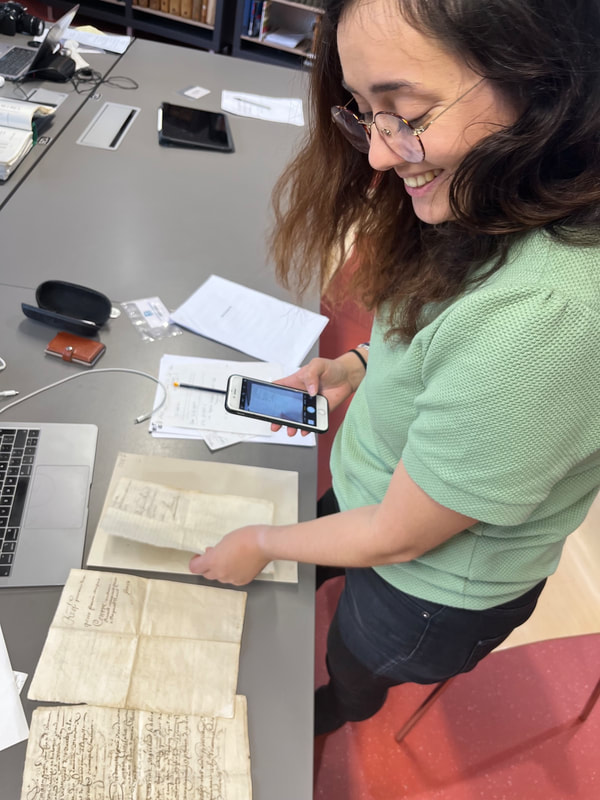

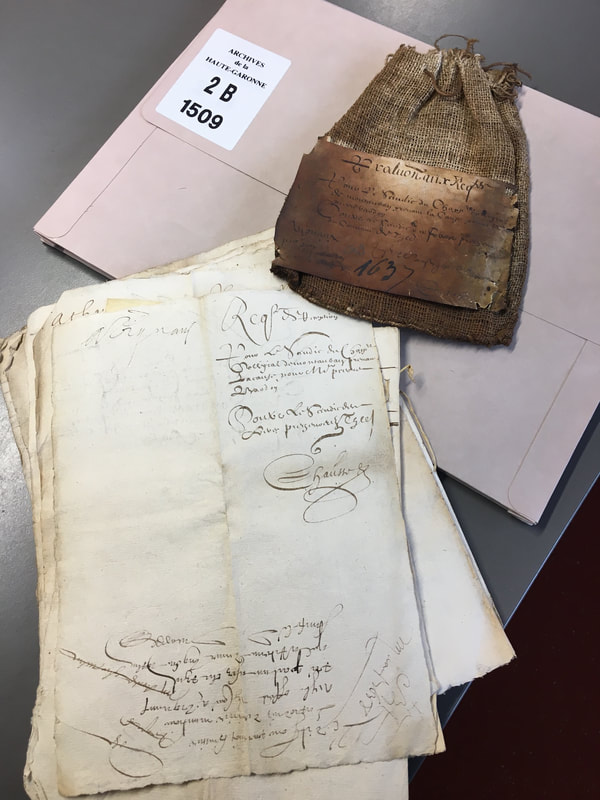

The Archives départementales de la Haute-Garonne are located in Toulouse, in a tall 1950s building that I was able to explore on the very first day, before even setting foot in the reading room. David and I were warmly welcomed by the deputy director of the archives and the person in charge of the fonds ancien. They quickly offered to show us where the trial bags are stocked, and it was an impressive sight. Long corridors of shelves are filled with over 100,000 bags. Each bag contains several judicial documents pertaining to criminal and civil trials in the jurisdiction of the Parlement of Toulouse, from the late sixteenth century until the French Revolution. Some of these bags came from the Chambre de l’Edit, the bipartisan court created for Protestant subjects in 1595 and abolished in 1679, six years before Protestantism was banned from the kingdom. Trial bags of the Parlement de Toulouse and the Chambre de l'édit in the stacks of the Archives départementales de la Haute-Garonne (ADHG). Photo: David van der Linden. With one look at the impressive stock preserved by the archives in Toulouse, it is safe to say there is a lot of work to be done. While around 15,000 bags have been inventoried, thousands of bags still remain untouched. But the sheer volume of bags also highlights the possibilities: the many crimes and conflicts unknown, the lives and stories still to uncover. The trial bags are a rich source of documentation about life in the seventeenth and eighteenth century in the Kingdom of France. They reveal in particular how justice was sought and served, what constituted a crime, and how legal procedures were understood by the population. Three trial bags from a case heard before the Chambre de l'édit in 1665, tied together with string. Source: ADHG, 3B 538. Photo: Sherilyn Bouyer. Fortunately, we already have access to a great number of bags. Regarding my project, around fifty bags handled by the bipartisan court have already been inventoried. During my three weeks in the reading room, I went through all of them. After reading a couple of bags, I decided to photograph them all, so as to have the time to transcribe them at home. I have also looked at cases which, although they involved Protestants, were not heard by the bipartisan court, but by the Parlement of Toulouse. I am eager to find out why this happened! Taking photos of the documents kept in the trial bags. Photo: David van der Linden. Each bag is different. I never knew what surprises the bags had in store for me. Some contained only two documents, while others had 150 documents. Some bags contained an inventory listing all the documents, so it was quickly clear that many bags are incomplete. While some cases seem straightforward, others mix different procedures in one bag. Some trial bags were actually connected to another bag, and that’s when the puzzle started to become even more complex. Documents can vary from a request of appeal made by the plaintiff to witness testimonies, but also include arrest warrants, royal arrests, reports drafted by the prosecutors, the hearing of plaintiffs and defendants, and extracts of judgements made by the lower courts. It is important to note, though, that trial bags do not usually contain the final judgement made by the court of appeal. Therefore, one of my future missions will be attempting to find the judgements of these cases in the large registers of arrests the archives in Toulouse have preserved. Documents in a trial bag from 1637. Source: ADHG, 2B 1509. Photo: Sherilyn Bouyer. These three weeks were fascinating. Fully immersed in the trial bags, I sometimes glanced at my reading room comrades – who were themselves on different missions – to hear their potential findings or their call for help to the staff of the archives. Overall, this first trip to the archive was very productive. I have now plenty of documents to transcribe and analyse. One of my future missions will also involve contextualising these cases by investigating the places in which the alleged crimes were committed, as well as the people involved. Therefore, travelling to municipal archives will be a priority of the project. The first bag I opened and read already took me to a municipal archive – but that’s a story for another day. – by Sherilyn Bouyer

Last October I left for my first trip to the archives in Toulouse. On my way there, I stopped in Paris to attend a three-day training in palaeography offered by the École Nationale des Chartes. The course, taught by Professor Marc Smith, aims to deepen the participants’ expertise in palaeography. Each day our group was given multiple difficult texts to transcribe, starting with sixteenth-century texts on the first day and ending with eighteenth-century texts on the last. We got the opportunity to work on notary acts, judicial documents, and letters, among others. Arrest by the chambre de l’édit du parlement de Paris, 8 May 1621. Source: BnF, ms. fr. 28409, no. 48. Each morning, Marc Smith began his class by introducing us to the history of handwriting, showing us how the Latin alphabet evolved throughout time and space. We learnt about the development of different hands, with changes caused by reforms or cultural exchanges. In 1632, for instance, the Parliament of Paris initiated a handwriting reform as documents had become almost illegible due to the poor handwriting of some scribes. One aspect of the course I particularly enjoyed was being shown the different models of writing that were taught and used throughout each century, notably the images demonstrating how to write (including the position of the body and the movement of the hand). It was also very interesting to get to know more about the community of maîtres-écrivains, or master scriveners. These masters were professionals united in a guild whose craft was the art of writing. One of their most notable works are the calligraphic collections they published, in which they demonstrated the many different ways a letter could be drawn. Marc Smith showed us several of these collections from different masters which he collected over the years, and we were lucky enough to browse through them. I am glad I was able to join this three-day training. It offered me valuable insight into the history of writing as well as practical advice how to deal with the most difficult documents. I believe this training would be valuable for any palaeographer and early modern historian in the making. The École Nationale des Chartes also offers a training for beginners. As for me, this course was the perfect foundation for my own archival research. – by Sherilyn Bouyer

On 6 and 7 October, medievalists and early modernists gathered in the beautiful salles of the Sorbonne in Paris to discuss an important topic: how did people in the past uphold the law in times of war and conflict? As the organizers François Foulonneau and Lucas Lehéricy stressed, historians have looked at military tribunals and court-martials, but for citizens it was even more important to be able to appeal to the law in times of war. This gave them a much-needed sense of security in uncertain times. The various speakers at the conference Juger l’ordinaire en temps extraordinaire all demonstrated that war never led to complete lawlessness. On the contrary, courts remained in function, people kept pleading their cases, and citizens collected evidence for future lawsuits. Sylvie Daubresse presenting on justice during the League. Photo: Rosanne Baars. The first day began with a panel on justice in times of crisis. What happened when a country suffers from internal divisions and civil war, such as during the Catholic League in sixteenth-century France? Sylvie Daubresse, for example, discussed court cases in Paris between 1589 and 1591. She showed that even in this period of crisis, common trials still took place. Diane Roussel spoke about the siege of Paris in 1590, and the notaries who kept doing their jobs. She also showed the irony of being held in prison in a besieged city: imprisoned à double tour. All speakers illustrated the continuing functioning of the law, even in those difficult times. Yet not all was fair in war, and even army commanders and soldiers were bound to the laws of war: excessive violence was severely punished. Valerie Toureille analysed the example of Aymerigot Marchès, who was persecuted for the excesses he had committed as an army commander during the Hundred Years’ War. The next day opened with a panel discussing the organization of legal institutions during times of war. Aurélien Peter showed that part of the Parisian court clerks went into exile to Tours during the troubles of the League, where they continued to work their cases. He also discussed the difficulty of reintegrating the returning clerks in the Parisian court once Henry IV had retaken the city, as they had to reconcile with their colleagues who had stayed. In the afternoon, David van der Linden presented the Building Peace project, discussing examples of transitional justice during the Wars of Religion, in particular efforts to punish the perpetrators of massacres. Tom Hamilton introduced Renée Chevalier, a noblewoman determined to get justice for war crimes committed during the Wars of Religion. Robert Descimon, finally, offered his reflections on these papers. Robert Descimon commenting on the papers of David van der Linden and Tom Hamilton. Photo: Rosanne Baars. The conference demonstrated that even in times of open warfare, life continues. Considered as la voix de justice, the courts needed to remain functioning at all times, something that people in pre-modern times were well aware of. As such, Juger l’ordinaire en temps extraordinaire was a successful and well-organized conference, which also provided great inspiration for the Building Peace project. As our team continues the research, we will explore to what extent Catholics and Protestants also clamored for justice once the Wars of Religion had ended. – by Rosanne Baars

Three Days of Massacre: Remembering and Forgetting the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, 1572–20227/6/2022 In May 2022 our team attended a three-day conference on the legacy, representations, and uses of the 1572 St Bartholomew’s Day massacre: Cet horrible massacre si renommé par toute l’Europe: Représentations et usages de la Saint Barthelemy en Europe et dans le Monde (1572–2022). Organised by the University of Sorbonne Nouvelle and Sorbonne University, the conference brought together scholars from history and literary studies. On the first day, we met at the Musée Carnavelet, a museum dedicated to the history of Paris, which includes a room on the French Wars of Religion that we had the opportunity to visit. The opening panel discussed the historiography of the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre since the nineteenth century, most notably the influence of Jules Michelet. Closing the panel, Jérémie Foa introduced his recent research on the identification and naming of the perpetrators of the massacre, revealing victims’ attempt to seek justice by denouncing the killers. Speakers of the second panel explored how the massacre has been mobilised, both through fictional works published in the late sixteenth century and in the collective memory of current Protestant communities. Caroline Trotot presented a paper on the memoirs of women who witnessed the massacre and recalled the event later in life, revealing the influence of different generations in creating a narrative of the massacre. The third panel took us outside the borders of early modern France, by discussing how news of the Parisian massacre was received in neighbouring states. Closing the first day, speakers on the fourth panel showed how St Bartholomew’s has been depicted in art and memorialised in the city’s public space. Plaque at the Île de la Cité commemorating the victims of the 1572 St Bartholomew's Day massacre. Photo: Rosanne Baars. The next day, we gathered at the Institut du Monde Anglophone. The opening panel included papers on the political uses of the massacre. Brian Sandberg discussed the concept of massacre and analysed the impact of the Paris bloodbath on the later Wars of Religion. Subsequent papers showed that the massacre was not only used during the wars, but was again mobilised for political purposes in the aftermath of the English Civil Wars of the seventeenth century, as well in the French Republic after the Commune and the Dreyfus affair. Hubert Bost presented a paper in which he analysed how memories of the massacre were mobilised by Huguenot communities in the eighteenth century. He argued that these memories were influenced by the experience of the Huguenots throughout the seventeenth century and were eventually tainted by the Revocation. Given that memories of the early stages of the conflict between Catholics and Protestants evolved with each generation, this raises some interesting questions for our own research project. How were the peace efforts of the late sixteenth century remembered by the second half of the seventeenth century? And did these memories affect the peacebuilding process of the decades leading up to the Revocation? Statue of Gaspard de Coligny, built in the nineteenth century at the Protestant church of the Oratoire du Louvre. Photo: David van der Linden. On the last day of the conference, speakers analysed the construction of memories of the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre in writings, most notably memoirs, historical accounts, and plays, but also by agents of information fabricating narratives of the event in foreign courts. In her paper on the memoirs of the Protestants, Alice Viaud argued that they were used to compensate for the lack of justice provided by the courts and to counter the edicts of pacification imposing silence on the violence of the conflicts. Finally, one of the highlights of the conference was a brilliant performance at the Oratoire du Louvre (by actors from the Studio Asnères) of The Massacre at Paris (1593) by the English playwright Christopher Marlowe. This stimulating conference thus demonstrates that 450 years on, the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre is still a fruitful topic for historical research. – by Sherilyn Bouyer

|

Blog

Welcome to our blog – stay tuned for regular updates on our project. Archives

February 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed