|

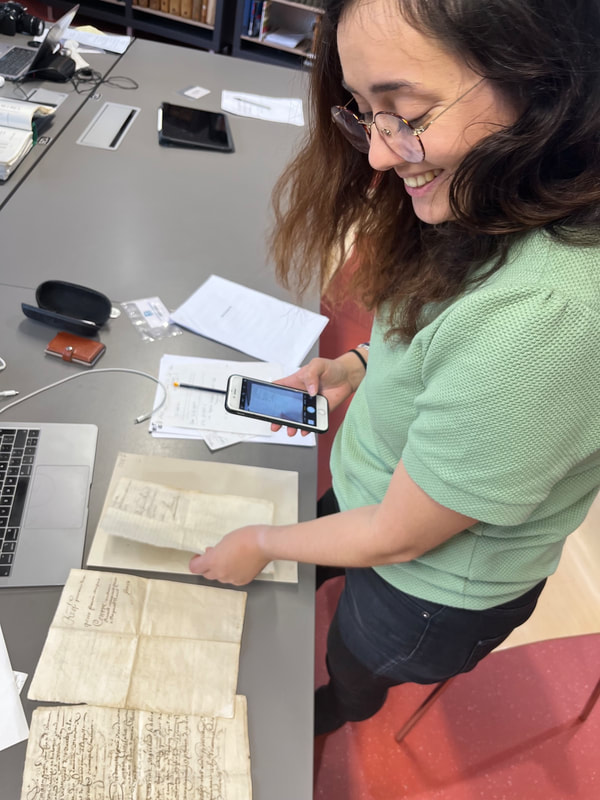

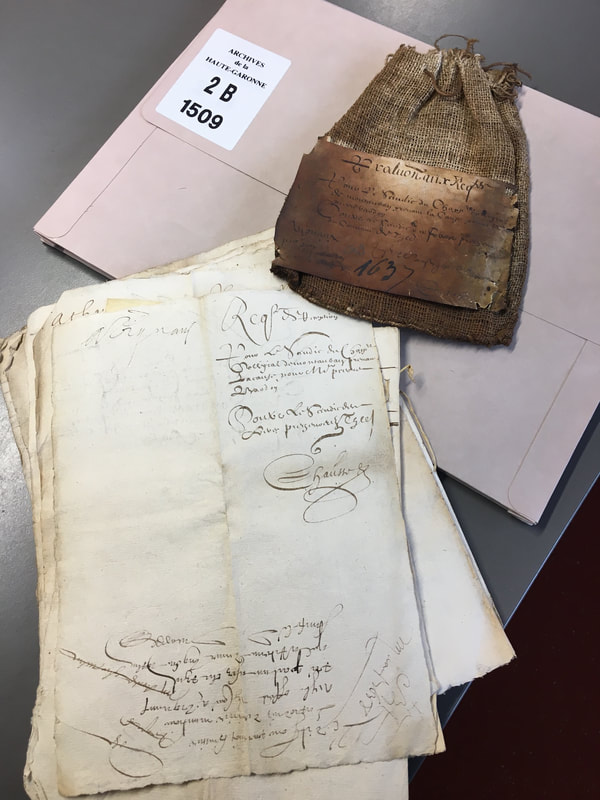

The Archives départementales de la Haute-Garonne are located in Toulouse, in a tall 1950s building that I was able to explore on the very first day, before even setting foot in the reading room. David and I were warmly welcomed by the deputy director of the archives and the person in charge of the fonds ancien. They quickly offered to show us where the trial bags are stocked, and it was an impressive sight. Long corridors of shelves are filled with over 100,000 bags. Each bag contains several judicial documents pertaining to criminal and civil trials in the jurisdiction of the Parlement of Toulouse, from the late sixteenth century until the French Revolution. Some of these bags came from the Chambre de l’Edit, the bipartisan court created for Protestant subjects in 1595 and abolished in 1679, six years before Protestantism was banned from the kingdom. Trial bags of the Parlement de Toulouse and the Chambre de l'édit in the stacks of the Archives départementales de la Haute-Garonne (ADHG). Photo: David van der Linden. With one look at the impressive stock preserved by the archives in Toulouse, it is safe to say there is a lot of work to be done. While around 15,000 bags have been inventoried, thousands of bags still remain untouched. But the sheer volume of bags also highlights the possibilities: the many crimes and conflicts unknown, the lives and stories still to uncover. The trial bags are a rich source of documentation about life in the seventeenth and eighteenth century in the Kingdom of France. They reveal in particular how justice was sought and served, what constituted a crime, and how legal procedures were understood by the population. Three trial bags from a case heard before the Chambre de l'édit in 1665, tied together with string. Source: ADHG, 3B 538. Photo: Sherilyn Bouyer. Fortunately, we already have access to a great number of bags. Regarding my project, around fifty bags handled by the bipartisan court have already been inventoried. During my three weeks in the reading room, I went through all of them. After reading a couple of bags, I decided to photograph them all, so as to have the time to transcribe them at home. I have also looked at cases which, although they involved Protestants, were not heard by the bipartisan court, but by the Parlement of Toulouse. I am eager to find out why this happened! Taking photos of the documents kept in the trial bags. Photo: David van der Linden. Each bag is different. I never knew what surprises the bags had in store for me. Some contained only two documents, while others had 150 documents. Some bags contained an inventory listing all the documents, so it was quickly clear that many bags are incomplete. While some cases seem straightforward, others mix different procedures in one bag. Some trial bags were actually connected to another bag, and that’s when the puzzle started to become even more complex. Documents can vary from a request of appeal made by the plaintiff to witness testimonies, but also include arrest warrants, royal arrests, reports drafted by the prosecutors, the hearing of plaintiffs and defendants, and extracts of judgements made by the lower courts. It is important to note, though, that trial bags do not usually contain the final judgement made by the court of appeal. Therefore, one of my future missions will be attempting to find the judgements of these cases in the large registers of arrests the archives in Toulouse have preserved. Documents in a trial bag from 1637. Source: ADHG, 2B 1509. Photo: Sherilyn Bouyer. These three weeks were fascinating. Fully immersed in the trial bags, I sometimes glanced at my reading room comrades – who were themselves on different missions – to hear their potential findings or their call for help to the staff of the archives. Overall, this first trip to the archive was very productive. I have now plenty of documents to transcribe and analyse. One of my future missions will also involve contextualising these cases by investigating the places in which the alleged crimes were committed, as well as the people involved. Therefore, travelling to municipal archives will be a priority of the project. The first bag I opened and read already took me to a municipal archive – but that’s a story for another day. – by Sherilyn Bouyer

0 Comments

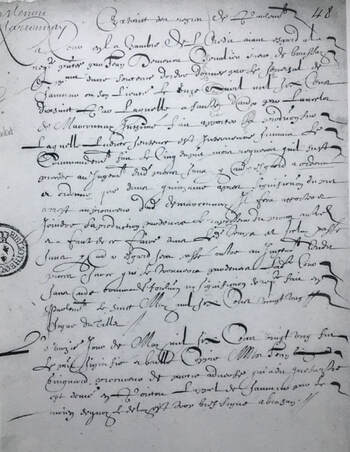

Last October I left for my first trip to the archives in Toulouse. On my way there, I stopped in Paris to attend a three-day training in palaeography offered by the École Nationale des Chartes. The course, taught by Professor Marc Smith, aims to deepen the participants’ expertise in palaeography. Each day our group was given multiple difficult texts to transcribe, starting with sixteenth-century texts on the first day and ending with eighteenth-century texts on the last. We got the opportunity to work on notary acts, judicial documents, and letters, among others. Arrest by the chambre de l’édit du parlement de Paris, 8 May 1621. Source: BnF, ms. fr. 28409, no. 48. Each morning, Marc Smith began his class by introducing us to the history of handwriting, showing us how the Latin alphabet evolved throughout time and space. We learnt about the development of different hands, with changes caused by reforms or cultural exchanges. In 1632, for instance, the Parliament of Paris initiated a handwriting reform as documents had become almost illegible due to the poor handwriting of some scribes. One aspect of the course I particularly enjoyed was being shown the different models of writing that were taught and used throughout each century, notably the images demonstrating how to write (including the position of the body and the movement of the hand). It was also very interesting to get to know more about the community of maîtres-écrivains, or master scriveners. These masters were professionals united in a guild whose craft was the art of writing. One of their most notable works are the calligraphic collections they published, in which they demonstrated the many different ways a letter could be drawn. Marc Smith showed us several of these collections from different masters which he collected over the years, and we were lucky enough to browse through them. I am glad I was able to join this three-day training. It offered me valuable insight into the history of writing as well as practical advice how to deal with the most difficult documents. I believe this training would be valuable for any palaeographer and early modern historian in the making. The École Nationale des Chartes also offers a training for beginners. As for me, this course was the perfect foundation for my own archival research. – by Sherilyn Bouyer

|

Blog

Welcome to our blog – stay tuned for regular updates on our project. Archives

February 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed