|

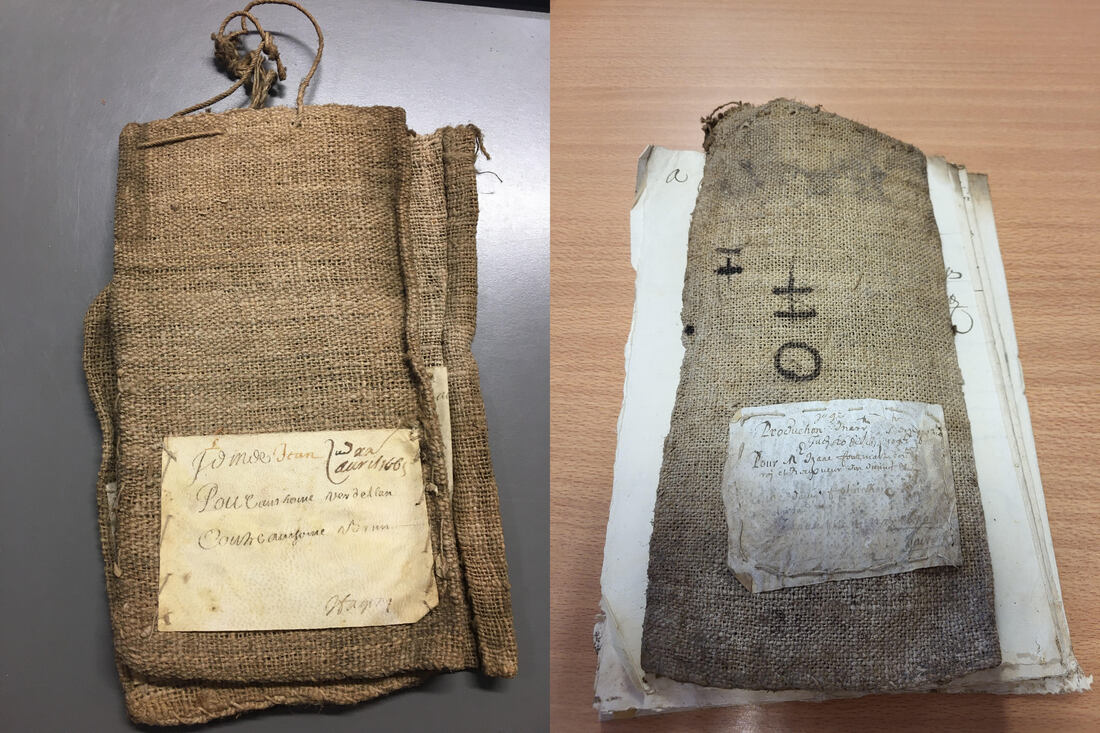

For five months I worked on the sorting, conservation, and cataloguing of trial bags in the Archives départementales de la Haute-Garonne (see also Archive diary of a PhD student – Part 2), as part of Sherilyn Bouyer's research project on the Chambre de l’Édit of Castres. The collection, transferred in 1955 to its current premises, was literally piled up in the current court of justice of Toulouse, previously the location of the Palais du Parlement. In the late eighteenth century, François Garipuy, a Toulouse astronomer and engineer, wrote a description of the palais and already noted the deplorable state of the documents, which he found “covered with dust and debris, almost rotten or devoured by rats.” Throughout the nineteenth century there were several attempts to catalogue the documents, but these were all abandoned due to the magnitude of the task. It was only in the late 1960s that the archives départementales were able to rely on the work of researchers and students to carry on the task of classifying all the trial bags. The endeavor remains colossal to this day, as it is estimated that 100,000 bags are currently stored in the archives. Around 15,000 of these bags have been inventoried since the late 1960s. As a result, today's archivists are faced with bags that are either partially classified – bags loosely tied together to form bundles of bags and scattered papers – or piled up in total chaos. Unfortunately for us, the bags from the seventeenth century, which would interest Sherilyn, are part of this chaos. Before I started my mission, Sherilyn had fifty-one bags pertaining to the Chambre de l’Edit. Therefore, my problem was both very simple and very complex: how to find as many bags from the chamber as possible within the limited time frame of five months? The unsorted mass of trial bags in the Palais du Parlement in 1955. Photo: Archives départementales de la Haute-Garonne. My first reaction to the magnitude of the task was to reflect on these previous attempts at classification. Was it possible that at some point in time bags from the Chambre de l’Édit had been shelved together? The idea did not seem absurd, and my hope from the beginning was to find a cluster of chambre bags, however small it might be. Discovering this hypothetical bundle required a systematic approach. Obviously, the first rule I followed was to consistently pick the bags next to the one I had chosen in the first place. The second approach involved covering the entire unit of four rows, in case a corner was dedicated to the chambre. To that end, I acted methodically to extract the bags. First, I simply noted the number of bags I had processed on each row in a notebook, indicating the location of the bags from the Chambre de l’Édit. I completed a full tour of the unit that way. Then, I improved this method by proceeding shelf by shelf, using an Excel spreadsheet and focusing on the places where I had already found bags from the Chambre de l’Édit. Finally, my strategy was to act efficiently to browse through as many bags as possible while producing solid and meticulous archival work. The archival work can roughly be divided in two parts. One is material, namely to improve and ensure the proper preservation of documents. The other is intellectual, meaning the analysis and cataloguing of the documents, ensuring their discoverability in the database of the archives, which researchers can consult. Although time was a problem, these two tasks had to remain my priority; I couldn't just take the documents out of their bags in search of Protestants. Regarding the preservation of the documents, one of my fundamental tasks was dusting. To not compromise the condition of the documents (dust can contain dormant mold), dusting had to be very meticulous, even if it was the most time-consuming task: dusting was carried out, page after page, on more than 4,000 documents (which could be between 2 and 60 pages). It takes about 10 to 45 minutes to dust off one bag, depending on the number of documents inside. To avoid losing too much time, then, the right bag should not be too heavy. However, if the bag is too thin, the task of analyzing and indexing could become a nightmare, especially if it contains only illegible documents or documents with little information. Moreover, a bag containing only two procedural pieces can be particularly disappointing for the researcher. The second part of my mission – analysis and indexing – has evolved significantly since the 1970s. Genevieve Douillard, former deputy director of the archives, and Jack Thomas, researcher and current president of the association Amis des Archives de la Haute-Garonne, first structured this procedure in the 1990s. Computerized since 2006, the significant work of Jean Maurel on criminal cases from the eighteenth century has shaped the current indexing sheets. The fine-grained indexing of facts, locations, and different levels of jurisdiction are the fundamental pieces of information he contributed to the specialized database that was made available for researchers. In addition to the (sometimes difficult) paleography, the art of good analysis and indexing lies in the archivist's ability to not to delve too deeply into details while still providing the most relevant information. While it was occasionally frustrating not to be able to continue analyzing certain bags, considerations of time and quantity had to remain my priority. It took me some time to figure out how to provide enough information without overdoing it, all the while remaining as meticulous as possible. An untreated trial bag and document (left); the same bag and document after conservation (right). Photo: Brandon Robidet. Unable to skip dusting and indexing, carefully considering my choices in the storeroom (where the bags are kept) was the only way to save time. Were there elements that distinguished, by their external appearance, the bags of the Chambre de l’Édit from the bags of the Parlement? With Sherilyn's help, I tried to carefully observe each of the photos she had taken during her research in the reading room. Certain elements quickly stood out: the canvas of a chambre bag is lighter, the parchment of its label (known as the évangile) surprisingly white, and the layout of its text much less standardized. These few criteria were enough to guide my eye in the storeroom. Markings and parchment labels (évangiles) on the trial bags. Photo: Brandon Robidet. In total I processed 462 bags during my five-month mission. Among these, eleven were produced by the Chambre de l’Édit and four by the Parlement of Toulouse directly concerning the chambre. At first glance, the number of cases of the bipartisan court seems negligible given the classified volume, but it still enriches Sherilyn Bouyer's source corpus by nearly 20%. With more time and resources, I am convinced that a larger cluster of bags from the Chambre de l’Édit could be found. Unfortunately, the regular processing of trial bags only occurs at the rate of one month each year, by students of the master in early modern history, who are not specialised in the history of the Parlement and the Chambre de l’Édit. This raises real conservation questions for documents that — at the current processing rate — will have to wait nearly 200 years to be all treated. This is the reason why the exceptional funding from the University of Groningen provided an important impulse for cataloguing by the Archives départmentales de la Haute-Garonne. It was also a chance for myself to work with these precious sources, but above all for research and for this wonderful collection, whose richness has, so far, only been scratched at the surface. – by Brandon Robidet, Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Blog

Welcome to our blog – stay tuned for regular updates on our project. Archives

February 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed